The “Great Trek” during World War II. Source: Canadian Mennonite.

When the woeful tale of Mennonite history is told, eventually you will hear the story of the “Great Trek.” Cold and wet, trekkers fought through knee-deep mud on a thousand-mile forced march to escape the Soviet hordes. To be sure there were plenty of heroic and tragic moments en route to humble the most resilient soul, yet missing from the story is one indisputable fact: Mennonites of the Great Trek were taking part in the murder and dispossession of Jewish and Polish people to their own benefit.

To understand what Mennonites call the “Great Trek” it’s important to understand the context of that dangerous and difficult journey from the Russian homelands to a place in today’s western Poland then known as the Warthegau (means region of the Warta river). This 17,000-square-mile area was to become the new homeland for all ethnic Germans from Russia.

To understand what Mennonites call the “Great Trek” it’s important to understand the context of that dangerous and difficult journey from the Russian homelands to a place in today’s western Poland then known as the Warthegau (means region of the Warta river). This 17,000-square-mile area was to become the new homeland for all ethnic Germans from Russia.

On August 23, 1939 Russia and Germany signed an agreement[1] to behave for the foreseeable future. Hidden somewhere in the fine print, maybe handwritten in the margin, was another agreement that if they could not behave, they would divide up central Europe instead of fighting over it. Poland was cut in half, and the Baltic states were divided between them. So you already know they had no intention of behaving.

Map showing the division of Poland according to the Molotov Ribbentrop Pact.

The Nazis’ mission to unite all Germans in a single state was hardwired into its political and racial philosophy so it was not unusual the Germans and Russians were already exchanging their unwanted peoples. The Volhynian and Galician Germans on the new Russian side of Poland were traded for the Ukrainians and White Russians on the new German side. Five hundred-fifty Mennonites agreed to resettle along the Warta River.

Even before the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941, when an expanding Germany’s position seemed more than secure, tens of thousands of Baltic, Bessarabian, Volhynian, and Galician Germans had already undergone their own peaceful mass relocations to “Greater” Germany.[2]

Lithuanian ethnic Germans arriving at the border greeted by a flash mob. Sign says “Welcome to Greater Germany.”

Warthegau was not the most appropriate place for a mass relocation of several million Russian Germans; it was already full of people. Of the nearly five million people already there, less than half a million were German, fewer still Jewish and the vast majority were Polish people.[3] However, it was in the right place, next door to where the “real” Germans lived.

So to house 550 Mennonites, 550 other people would have to go away.

Expelled Poles leaving home with what they could carry. That looks like about 550 people.

The Nazis expected this problem even before beginning World War Two. They established an elaborate and effective organization known as the Volksdeutsche Mittelstelle (abbreviated as VoMi = Coordination Centre for Ethnic Germans) to work through the challenges ahead. VoMi was originally located within the Nazi Party structure, but it was soon apparent a stronger hand was needed and SS chief Heinrich Himmler took charge of resettling ethnic Germans from Russia. The VoMi provided resettlement services such as housing, financing, employment, cultural and educational services, health care, and security. As a Russian German, if you made it to Warthegau, everything would be okay.

Heinrich Himmler – before, during and after.

Himmler sent special sub-unit of 200-300 men and women to the ethnic German communities of Ukraine to prepare them for the journey to Warthegau. Under the command of Horst Hoffmeyer this sub-unit of VoMi known as Sonderkommando R, established schools, health units, partisan protection, Hitler youth groups, cultural retraining, Soviet detoxification, etc. This was a hearts and minds mission with a bullet, ethnic Germans had to show they qualified for entry in Warthegau. Any Jews that had escaped the Einsatzgruppen were murdered outright, as were any ethnic Germans suspected of having communist leanings. Ethnic Germans who showed enthusiasm were given extra food, clothing and other privileges. When Mennonites left for Warthegau, they knew the Nazi policies and could not be confused about how the new housing they were promised was acquired.

Einsatzgruppe executing a Jewish family near Ivanhorod, Chernihivs’ka oblast, Ukraine in 1942. Who are the unseen holding weapons at the left of the photo? Could they be ethnic Germans? Mennonites?

In Transnistria, the VoMi made Germans by creating killers – the Volksdeutsche Selbstschutz committed mass murder to prove their allegiance to Nazidom and thus were considered Aryan enough.[4]

Hermann Rossner was the VoMi man in the Mennonite stronghold of Halbstadt, Molochna.[5]

According to Rossner:

- First of all, the schools had to be brought into operation again.

- The hospitals in Halbstadt and Orloff also had to be made usable again. Eighty-four German Red Cross nurses came from Germany and dealt with the nutritional as well as medical care of the ethnic Germans.

- A teacher training institute established, headed by the Swabian national poet and Stuttgart town councilor [Ratsherr] Karl Götz.

- In Halbstadt a pharmacy was set up, and the German hospital acquired operating room equipment from Germany.[6],[7]

In Halbstadt, Rossner worked with B.H. Unruh, Mennonite intellectual, theologian, professor and devoted Nazi. It is said he would not tolerate even the slightest criticism of the Nazis.[8] Unruh, representing the Mennonite community in Russia, fostered close ties with the Nazi regime and met with Himmler and Hoffmeyer, two of the most abhorrent killers of the war, to succor their approval and to negotiate the right of Mennonite soldiers to solemnly affirm their allegiance to the Führer rather than swear it. According to Karl Götz[9], “the Reich Chief of the SS approved of the behavior and attitude of the Mennonites.”[10] Who could ask for more?

Mennonite woman and child on the Great Trek.

When it was time to begin the trek, it was voluntary.

Rossner further recalls that in 1943, no one in the Molotschna was required to leave. Those who wanted to stay could stay. He believed that Dr. Klassen[11] of Halbstadt had stayed, but he did not know for certain anymore.[12]

People knew they couldn’t stay in Russia, but it would be wrong to characterize the Great Trek as a forced march. Nazis provided soldiers for security and nurses for medical and nutritional care. It was a kind of rescue mission, but the kind where you had to make a deal with the devil. Mennonites could not be unaware of what was happening in the Warthegau in anticipation of their arrival. B.H. Unruh had met with Himmler and Hoffmeyer in Lodz, (Litzmannstadt was its Nazi name), while the killing was taking place. What would they think upon entering their new homes and finding a half-eaten meal on the table, the childrens’ beds unmade?

Already during their two-year occupation of Ukraine, the German forces had assumed a caretaking role within Mennonite communities and even for specific families. In light of the absence of adult males in many households, German soldiers came to be viewed as protectors and also formed romantic relationships with young Mennonite women and sometimes with widows as well. On the trek, some of these men continued to play the role of protector and, when it came to fixing wagons, controlling horses, and enforcing order, replaced the males that had been removed from so many families.[13]

In Molochna trekkers had three days to prepare, and when they left on September 12, 1943[14], the train of covered wagons was 20 kilometres long.[15] For Mennonites and others who lived in cities under military threat, Nazis provided trains, sometimes travelling in cattle cars bedded with straw.[16]

Peasants from eastern Poland happy to arrive in Warthegau May 1940.

The journey was fraught with struggle and danger. In her excellent exposé of the role of women on the journey, Marlene Epp quotes Helene Dueck:

[The roads] “were a sea of mud. It is impossible to describe them and the hardships they caused to the trekers[sic.]. Often up to the axles in mud. The horses would slip and fall. Often even the whip would not get them up. We would push the wagon, walking deep in mud ourselves. Faces, hands, clothing, shoes-everything full of mud and wet. We were cold and wet, hungry and had little strength left. No men to help us.”[17]

The expelled Poles – I wonder how long that bread lasted.

As difficult as the trek was for the Mennonite women and children of German descent, it was immeasurably better than that suffered by the non-Germanic population.

With 2,000 wagons full of ethnic Germans on the way, Nazi officials in Poland had to find places for them. The heart of the German plan was dark but simple. Kill anyone deemed an enemy, and enslave anyone else until they are no longer useful, and then kill them. The first Nazi extermination camp—Chełmno—was built in Warthegau less than an hour’s drive north of Lodz.

The first gassing at Chełmno took place on 8 December 1941. It was judged a success.[18]

The victims were Jewish villagers from several nearby communities. They arrived by train and then driven by whips into a mill on the Warta River in the village of Zawadki. Left overnight without food or water, in the morning they were loaded into trucks whose exhausts exited into the sealed cargo compartment. By the time the trucks arrived at a hole in the nearby forest the victims were dead. The bodies were unloaded and the trucks went back for more.[19]

In all, five lorries were used, three of which held up to 150 people, and two up to 100. By noon the whole trainload had been destroyed.[20]

Burned-out Magirus-Deutz furniture mover van near Chełmno extermination camp.

Arrival in the Warthegau

German caption read: “New village in the Wartheland. Only the two houses in the middle remain, the rest of the old village completely burnt by the Poles in September 1939. In just a few years, new villages will have sprung up all over the Wartheland, from which a new East German peasantry will live and prosper.”

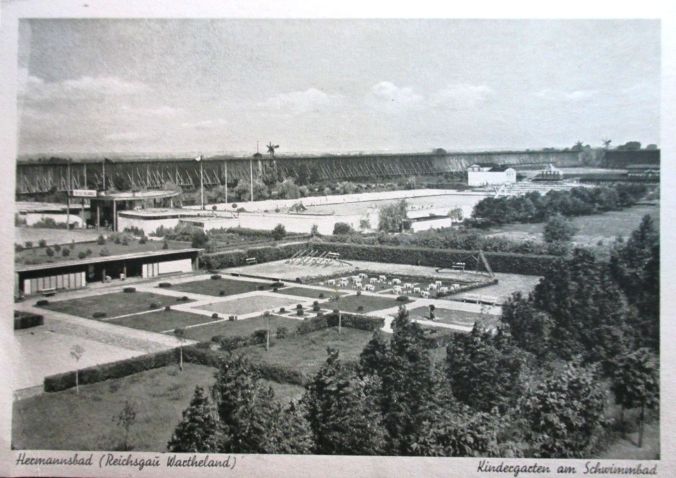

Water park, spa and swimming pool in Wartheland.

Baltic Germans checking out the new digs in 1939.

Everyone received a framed photo of the Führer

Upon arriving in Litzmannstadt (Lodz) trekkers were deloused then subjected to an intensive screening process often lasting two days at eight screening stations at the Einwanderungszentralstelle or EWZ (Main Immigration Office). The results of the process determined where they would find themselves in the New Germany and how they would live. At each station 6-8 officials scrutinized family documents, their history, their previous political involvements and their occupational potential. Potential immigrants where photographed and physically examined and subjected to other hokey racial hoo-ha.

Registering at the EWZ. Source: SS- und Polizeiführer Lublin

One particular aspect of these investigations would have appealed to Mennonites: this was also where compensation for property left in Russia was determined.

German immigrants were lured back and compensated with farms, workshops and houses, including inventory that had belonged to displaced ‘Poles and Jews’. [21] The amount of property left behind was ascertained, and the resettlers were issued receipts stating how much and what type of compensation they were to receive.[22]

These immigrants received a nice farm for their trouble.

That Mennonites on the Great Trek had an understanding with Hitler must have made the hardship of the journey more tolerable. In the end, they received no compensation though, according to Eric Schmaltz, leaving the German government to deal with the issue in the 1950s.[23]

In Warthegau Mennonites practically fell over themselves to prove their German, not Dutch[24], ancestry, completing surveys, or racial passports, tracing their “German” forbears to their beginnings in Russia. It wouldn’t be long before many of these same Mennonites would insist they were Dutch people. But let’s not get ahead of ourselves.

For most citizens of Nazi Germany, including the vast majority of its Mennonite population, genealogy provided a valuable means of proving Aryan ancestry, granting individuals demonstrating “pure” Germanic heritage access to generous political and welfare benefits, while also entrenching racism as a normal category of social division.[25]

Those who received favorable designations … were given generous access to food, clothing, and other benefits, while at the same time, millions of those placed in less desirable categories, like “Russian,” “Polish,” or “Jewish,” were subjected to persecution, forced labor, and mass murder.[26]

Mennonites could not have been unaware of the Nazi brutality and genocide that was occurring in nearby concentration and extermination camps, and many of them believed a German victory was the will of God.[27]

German refugees fleeing to the west – the Great Trek part two.

The Flight

In Warthegau, Mennonites lived in the houses of murdered and dispossessed Jews and Poles. Things were fine.

Mennonites received housing and work placements and were also recruited into various military and non-military wartime services. Women found work on farms, in factories and offices, and because of their language facility in Russian and German, were valued as interpreters for the military effort. The feeling of temporary stability was such that some young women were able to enter school for training in teaching, nursing, and midwifery skills. [28]

Refugees fleeing the Soviet approach.

After eight months Soviet military advances required a second and more desperate “trek” to safety. Now all ethnic Germans and German sympathizers were on the run.

The second phase of the Mennonite refugee movement across war-torn Europe occurred in the last six months of the war. The ‘flight’ westward to escape the Soviet army advancing into eastern Europe in the winter of 1944-45 drew another population of Mennonites into the refugee movement. These were Mennonites numbering close to 12,000 in 1939, born and raised in Poland, East and West Prussia, and the City of Danzig.[29]

Thousands of evacuees died trying to reach German rescue ships in the Gulf of Danzig and Baltic Sea, where the dangers of crossing treacherous ice-covered lagoons were compounded by strafing from Soviet bombers from above and the threat of Soviet submarines and mines below.[30]

Many people clung to the outside of trains for hundreds of kilometres, despite the severe cold of winter. Individuals and families who were unable to obtain transport by train, truck, or wagon, simply fled on foot in a direction that would take them away from the sounds of approaching Soviet tanks and aircraft.[31]

And although the west was a goal for Mennonites and others, few had any idea of their final destination. In the flight ahead of the Red Army, the single desire of many refugees was to keep moving.[32]

It turns out the one millionth German in Warthegau was a 39-year-old farmer from Hoffental, 70 kilometres south of Gerhard’s home village of Nikolaipol. After this private meeting with Arthur Greiser (Right), the Gauleiter in charge of Warthegau, and Heinz Reinefarth (Centre), whose SS troop killed 60,000 civilians in Warsaw in two days, the unnamed immigrant was introduced to a crowd of 30,000 voluntary attendees at an evening celebration. Greiser was executed after the war, but Reinefahrt was never prosecuted and enjoyed a fine political and legal career in post-war Germany, dying in his mansion on the island of Sylt in 1979. Fot. Hoffmann 17.3.44

* * * * *

Gerhard was out there too. As far as I know, he was in Berlin attending Wehrmacht interpreter school.

NOTES

[1] Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact.

[2] Schmaltz, Eric J., The “Long Trek”: The SS Population Transfer of Ukrainian Germans to the Polish Warthegau and Its Consequences, 1943-1944, cited in https://library.ndsu.edu/grhc/articles/ journals/schmaltz.html, accessed April 20, 2018.

[3] Numbers given were 4.2 million Poles, 400,000 Jews, and 325,000 were Germans in Czesław Madajczyk. Polityka III Rzeszy w okupowanej Polsce, pages 234–286, volume 1, Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe, Warszawa, 1970 cited in https://www.wikiwand.com/en /Polish_areas_annexed_by_Nazi_Germany#/Demographics accessed April 20, 2018.

[4] Steinhart, Eric, The Holocaust and the Germanization of Ukraine, Cambridge University Press, 2015, page 11.

[5] Gerlach, Horst, Mennonites, the Molotschna, and the Volksdeutsche Mittelstelle in the Second World War, Translated by John D. Thiesen, Mennonite Life, September 1986, page 5.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Dr. Johann Klassen, who selected 100 disabled patients for execution, was the doctor in the Halbstadt hospital.

[8] MennLex: Biography of Unruh, Benjamin Heinrich, http://www.mennlex.de/doku.php?id=art:unruh_benjamin_heinrich, accessed April 23, 2018.

[9] This would be the same Karl Götz for whom Mennonites of Steinbach came out in droves to hear the Nazi gospel in 1936.

[10] Götz, Karl, Die Mennoniten, 1944, Bundesarchiv Koblenz [Federal Archives in Koblenz], R. 69/215, p. 11, cited in Gerlach, page 6.

[11] Dr. Johann Klassen who was involved in the murder of 100 disabled patients.

[12] Gerlach, op. cit., page 8.

[13] Epp, Marlene, Moving Forward, Looking Backward: The ‘Great Trek’ from the Soviet Union, 1943-45, Journal of Mennonite Studies Vol. 16, 1998, page 66

[14] Epp, op. cit., page 61.

[15] Neufeld, Jacob A., Path of Thorns: Soviet Mennonite Life under Communist and Nazi Rule, University of Toronto Press, 2014.

[16] Schmaltz, op. cit.

[17] Dueck, Helene, Letter to T.D. Regehr, 16 March 1989,20, cited in Epp, op. cit., page 61.

[18] Gilbert, Martin, Atlas of the Holocaust, Lester Publishing Limited, Toronto, 1988, 1993, page 83.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Teunissen, Harrie, Lebensraum and Getto, Karte der Warthegau, Plane von Litzmannstadt, Lecture for the 18th Cartography Historical Colloquium, 15.-17. September 2016 at the Institute for History of the University of Vienna, Leiden/Wien, September 2016, http://www.siger.org/lebensraumundgetto/, slide 11

[22] Lumans, Valdis O., Himmler’s Auxiliaries: The Volksdeutsche Mittelstelle and the German National Minorities of Europe, 1933-1945 (Chapel Hill and London: The University of North Carolina Press, 1993), page 190 cited in Schmaltz, op. cit.

[23] Schmaltz, footnote 57.

[24] They would return to the Dutch gambit very shortly.

[25] Goossen, Benjamin W., From Aryanism to Anabaptism: Nazi Race Science and the Language of Mennonite Ethnicity, The Mennonite Quarterly Review 90 April 2016, page 136.

[26] Goossen, op cit., page 150.

[27] Schroeder, Steve, Mennonite-Nazi Collaboration and Coming to Terms With the Past: European Mennonites and the MCC, 1945-1950, Conrad Grebel Review, Spring 2003, page 7.

[28] Epp, op. cit., page 63.

[29] Epp, op. cit., page 68.

[30] Ibid.

[31] Epp, op. cit., page 69.

[32] Ibid.