For Gerhard, his “capture” by the German army had been the fulfillment of a dream. It’s doubtful his conscience struggled for even a moment. By 1944, Gerhard had already served as a driver in various supply columns, as interpreter for the military police interrogating prisoners, and as mailman delivering letters from home to soldiers on the scattered outposts of the front. Years earlier he would have been kicked out of church and shunned by the community, but now he was a lance corporal in the Wehrmacht. One wonders what would the Mennonites think about Gerhard now?

Gerhard’s journey took him to the German army, and he embraced his duties, whatever they were. It may not be a surprise Gerhard was not the only Mennonite who embraced the New Order. Mennonites of Prussia, Germany, Russia, and North America, having lived for so long on the slippery slope of accommodation, had finally dropped off the edge. Their response to the rising Nazism ran the gamut from mild disinterest to enthusiastic participation and perpetration.

Did Gerhard’s people refuse to take part and stay true to their pacifistic beliefs? Did they have any crisis of conscience? Or was it best to pocket your principles and go with the flow? For Gerhard, joining the German army was the culmination of “a great wish,” for how many other Mennonites were the Nazis seen as the solution, perhaps as the tool of revenge for Stalin’s excesses?

Prussian Mennonites were enthusiastic supporters and “…not one able-bodied Mennonite man of draft age in all of Germany refused conscription”[1] in the Second World War. Some even joined the SS.[2]

While the Mennonites today share in the struggles of the broader German nation when coming to terms with this part of their history, they must also deal with the added conundrum of having compromised fundamental tenets of their own Mennonite faith.”[3]

At one point in their history, Mennonites saw themselves “as the true successors of the one true church, whose defining characteristic was that of being a wehrlose Christen [pacifist Christian].”[4] But by World War One “the notion of non-resistance was virtually non-existent among Prussian Mennonites.”[5]

Hitler’s portrait and his motto in a Mennonite church in Paraguay – “The common good before individual good.”

Years earlier, the concept of non-resistance was deleted from the Danzig Mennonite Church constitution: “Whenever the fatherland requires military service we allow the individual conscience of each member to serve in that form which satisfies him most.”[6] This is the same justification Russian Mennonites used to build their own army.

By 1933, “most [Prussian] Mennonites … had aligned themselves with the Nazi movement largely because of their perceived victimization under the Versailles settlement, and due to the anti-Bolshevist sentiment emanating from the martyrdom of their brothers in Russia.”[7] As sworn opponents of the Soviet government and as an erstwhile military force, martyrdom is hardly an appropriate term. The Versailles treaty placed an international border and tariffs between Prussian Mennonites and their markets. Hitler promised to unite all Germans and bailed out the struggling farmers who subsequently prospered.[8] Economics served as a motivating factor for Mennonite support of Adolf Hitler.

By 1940, the West Prussian Mennonite Conference declared that “the conference will not do anything that gives even the faintest appearance of opposition to the policy of our Fuehrer.”[9]

* * * * *

Stutthof

One of the most notorious extermination camps of the Third Reich, Stutthof, was located “in an area with the highest density of Mennonite residents of any place in the world.”[10] It was the first concentration camp established outside of German territory and the last one to be liberated.[11] Of the 110,000 people sent to Stutthof, 85,000 died there. Here people were gassed, 100 at a time, here corpses were converted into soap, and here was the beginning of the 1,500 kilometre death march that killed half of the 50,000 remaining prisoners.[12]

Stutthof Concentration Camp in the Mennonite homeland.

In Stutthof itself, tens of thousands of prisoners died of dysentery, typhus and starvation. Others were brutally clubbed to death while working in the nearby forests, or sadistically drowned in the mud. Many were killed by means of phenoil injections, and their bodies then burned in the crematorium, in specially designed ‘high capacity’ ovens.[13]

… at least two Mennonites were known to have served as guards, many Polish Mennonite farmers used inmates as cheap labour under the oversight of SS guards, a major Mennonite factory was constructed largely with concentration camp labour, and most Mennonites in the area were not all that upset or even curious about what went on at Stutthof behind the wall of official secrecy.”[14]

Mennonites have often relied on their surnames to identify as members of their privileged group. Because they lived in enclaves and resisted cultural exchange such as intermarriage, Mennonites had a few surnames. Today we can use that logic for the same purpose. Here are some Mennonite surnames that “turn up on lists of former camp guards during postwar war crimes trials: Johannes Görtz, eight years imprisonment; Heinz Löwen, five years imprisonment; Johannes Wall[15], five years imprisonment; Fritz Peters, death sentence.”[16]

Heinz Löwen, was one of the few guards actually tried after the war in Danzig and given a relatively light sentence of five years.[17]

A forced labour crew was guarded by an SS contingent commanded by SS-Rottenführer Johannes Wall. Witnesses at a court trial testified to his kindly treatment of prisoners. He had allowed them to visit with family and friends. But in 1942 Wall was transferred to the Dachau Concentration Camp, where his behavior was less benign. A district court in Gdansk found him guilty, ordering a five-year prison term and suspending his citizenship rights for five years. He died in prison in 1948.[18]

Emilie Harms served as a work supervisor of young Jewish inmates from the Groß-Rosen concentration camp. They were assigned to perform dangerous work in the Dynamit-Action-Gesellschaft, formerly Alfred Nobel & Co., at the outlying camp in Christianstadt near Breslau. While some of the women below her behaved brutally, there is no evidence of any complaints against Harms herself.[19]

Another likely Mennonite, a man named Schröder, turned up in the personnel records of the Stutthof outlying camp at Malken. Schröder was one of twenty SS guards notorious for their brutal treatment of 1,000 Jewish women assigned, among other tasks, to build dykes and bring in the beet harvest. Most of the women were shot outright when they could no longer work. Schröder, the SS guard, was tried after the war for murder along with a number of his colleagues, but the case was dismissed … .[20]

One gets the impression from Gerlach’s[21] anecdotal interviews with several native Mennonite farmers in the Vistula delta that most of them took advantage of the temporary labour of Stutthof inmates—Jews and non-Jews, male and female—to perform hard work during harvest time and for other duties on their farms. No one paid them any salaries although they generally appear to have been fed fairly well and housed in hay barns or even farmhouses. In some cases camp staff brought the inmates food at work, especially if this was some place other than a farm. To be sure, the farmers had to pay the camps for the use of inmate labour—probably at a rate considerably less than the going rate of RM 0.50 per hour for unskilled labour. But even though some Mennonites then and today are not quite willing to admit that fact, the thought that this kind of compulsory work was anything less than slave labor is absurd.[22]

A fairly large camp in Zeyersvorderkampen employed some eighty Jewish women as field hands as well as numerous craftsmen who were transferred from Stutthof between November 1939 and June 1940. Kornelius Fast, the Mennonite council chairperson (Vorsteher) of the town, oversaw the project and was therefore in a position to furnish slave workers requested by all the farmers and the town administrators in the area.[23]

A Mennonite farmer named Otto Froese received a contingent of inmate workers from the camp at Störbuderkampe, but the guard who came with them was unsatisfactory to Froese, who had him replaced with a tougher character.[24]

Two Mennonite estate owners named Wiens and Funk reportedly treated their forced laborers from a Stutthof outlying camp in Jankendorf quite well even though they housed them in barns with the cattle and in shed closets with machine tools.[25]

The outlying camp of Neuteicherhinterfeld—probably an offshoot of the large camp in Danzig, housed in the Viktoria-Schule—contracted with Stutthof to supply workers to various farms in the fall of 1939, including that of a man named Schröder, likely a Mennonite farmer.[26]

In the fall of 1939, a Mennonite, P. Epp, the mayor (Ortsvorsteher) of Herrenhagen, employed forced labourers from Stutthof.[27]

There a farmer with the Mennonite name of Riesen contracted for the labour of some twenty inmates who did field work in July and August 1943, later valued at 420 Reichsmark, paid to the SS administration in Stutthof.[28]

In Klein Lichtenau, two Mennonite farmers, K. Wiebe and Erich Claassen, contracted for forced labour in the fall of 1939.[29]

Mennonite businessmen also were not immune to the allure of free, or nearly free, labour.

A Mennonite builder, Gerhard Epp, for example, not only leased 300 Jewish slave laborers at Stutthof to build a new factory near the camp but also served as some sort of general contractor to the SS in assuming responsibility for the construction of all buildings on the premises. It is not much of an exaggeration to say that a Mennonite built the barracks for the first concentration camp on non-German soil.[30]

… the inmates marched the two kilometers to the building site every morning and back again at night. Meals were delivered to the site from the camp kitchens. Today Epp & Wiebe GmbH in Preetz [http://www.epp-wiebe.de/ ] is a thriving business in the field of heating and air conditioning equipment.[31] Gerhard Epp’s machine factory in the village of Stutthof was certainly the largest Mennonite employer of slave labour. Epp had endeared himself to the regime by building a home for the Hitler Youth in Tiegenhof. His main factory employed some 500 prisoners from at least 1942 to the end of the war and focused on the production of various kinds of armaments such as small firearms. Epp’s factory, along with others, evacuated machinery and stock supplies to the West in order to continue producing armaments in a place safe from the advancing Russian Army.[32]

In August 1943 four Mennonite business owners owed the following amounts to the Stutthof concentration camp for the use of slave labour: “Peter Neufeld of Pillau, 270 RM; Heinrich Wiens II of Kalteherberge, 1,308 RM; Eduard Reimer of Roschkenkampe, 2,804 RM; and Gerhard Epp of Petershagen, 460 RM.” At a rate of 2 RM per day, slave labour in these businesses was for more than casual employment.[33]

The population in this region was therefore fully exposed to the slave labour of Stutthof inmates; and business owners and farmers made full use of the opportunities to exploit cheap labour while the SS administration reaped huge financial benefits. Surveying the evidence from the outlying camps, the degree and depth of Mennonite involvement with forced labour extracted from the inmates and their role in the genocide that followed becomes clearer.[34]

Russia

Russian Mennonites were also on this terrible journey. How well the Nazis provided avenues for their lust for revenge! Many who had eluded the transport to the labour army embraced the German army, as Gerhard did, as it raced eastward across the continent. Like their co-religionists in Poland before them, a majority of Mennonites in Ukraine greeted Hitler’s armies as liberators. “It was a joy for us all,” one inhabitant of the Molochna Mennonite colony recalled, “as we greeted the German soldiers for the first time and were able to speak of our sufferings and express joy to them in the German language.”[35]

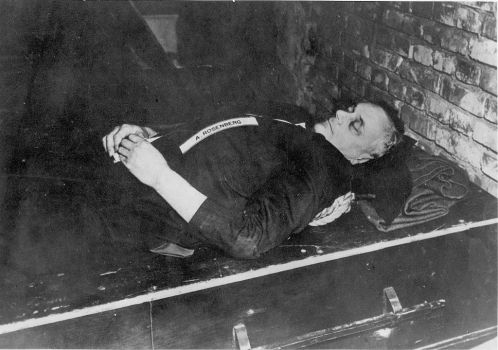

Visits by high ranking Nazi dignitaries brought the Mennonites out in droves [see it on video at https://youtu.be/WKPoJLXMhW8%5D. In Khortitsa they lined the streets, enthusiastically sieg-heiling Reichsminister Alfred Rosenberg and his entourage at every opportunity.

Alfred Rosenberg in his various stages of existence.

In Molochna, the head of the SS and the second most powerful man in the Third Reich, Heinrich Himmler, reviewed the ethnic German cavalry squadron as well as Halbstadt’s very own Hitler Youth contingent. That evening the ladies choir performed a few numbers and they all prayed for God’s blessing.

Heinrich Himmler reviewing Molochna’s Hitler Youth detachment.

The Mennonites encountered by the German army had suffered at the hands of the Bolshevik revolution and their martyr complex was ready to explode. Too many Jews were in positions of power in the new Communist system. They ran the collectives, they had positions in local government and in the secret police. Jews, Bolsheviks, there was no difference. Now that the forces of justice had arrived it was time to set things right.

Anna Sudermann, for example, reported that she encountered them [Jews] all too frequently in the judicial system, in the role of interrogating judges and states attorneys and police chiefs. Hence, it was easy to regard Jews as part of the Soviet class enemy on whom raw revenge could now be exacted under the guise of official police work, since few Mennonites were probably keen enough to distinguish between normal policing and outright murder committed under the auspices of the Einsatzkommando [mobile killing teams]. But how they ultimately justified their actions of murder against innocent civilians, women and children among them, is a dark mystery that cries out for a deeper explanation.[36]

Himmler, Heinrich, at the evening event of his visit to the ethnic Germans in Halbstadt October 31, 1942.

The Nazis promised to return things to the way they were in the heyday of the Mennonite commonwealth. No more collective farms, private lands returned to estate owners, farm equipment was returned to the “right” kind of people. Clothing was now abundantly available, sometimes with blood stains and bullet holes still visible;[37] and German cultural education was emphasized to “peel back years of Soviet contamination.”[38]

It might be easy to believe there were two different types of killers on the Eastern Front. There were the men of the Wehrmacht, performing their duties in a soldierly fashion; if killing was required it would be a soldierly killing, soldier to soldier. There were also those ghastly homicidal maniacs who killed whoever they wished whenever and however they wished. They stripped their victims naked, laid them down in shallow trenches to receive the bullet, they were the other kind. There was no satisfying their murderous lust. They would be the Waffen SS, the Einsatzgruppen, the Sicherheitsdienst, and other police functionaries. To accept this idea would be to ignore the founding principle of the Third Reich – Gleichschaltung. Synchronicity. The entire nation synchronized its every action to further the goals of the Third Reich. And if there was any doubt as to the goals of the Third Reich Field Marshal Walther von Reichenau clarified the matter on October 10, 1941 when he issued the following order to the Sixth Army on the Eastern Front:

The most important objective of this campaign against the Jewish-Bolshevik system is the complete destruction of its sources of power and the extermination of the Asiatic influence in European civilization … In this eastern theatre, the soldier is not only a man fighting in accordance with the rules of the art of war, but also the ruthless standard bearer of a national conception … For this reason the soldier must learn fully to appreciate the necessity for the severe but just retribution that must be meted out to the subhuman species of Jewry.[39]

Mennonites and other ethnic Germans in Halbstadt, the “capital city” of Molochna, established a self-defense force similar to the Selbstschutz of the First World War. By now soldiering came easily. They also mounted a cavalry force of 500 Protestants, Catholics and Mennonites, which became part of the SS Division Florian Geyer, a division involved in the anti-partisan operations behind the front line and killed tens of thousands of the civilian population.[40]

Members of a Mennonite Waffen SS squadron in Ukraine’s Molotschna colony 1943 Credit Harry Loewen, ed., Long Road to Freedom Mennonites Escape the Land of Suffering Kitchener, ON Pandora Press, 2000

In the Mennonite homelands of the Khortitsa and Molochna colonies, the Einsatzgruppen, which followed in the wake of the regular army, were conducting their murderous business, and it seems everyone knew what was happening. After the arrival of the German army in a village all Jews were registered. Once registered it was only a matter of time before they were no longer there.

Visions for racially homogeneous Mennonite settlements under fascist rule found realization in Nazi-occupied Ukraine. Here, Heinrich Himmler (third from right), head of the SS and an architect of the Holocaust, at a flag raising in the Molotschna Mennonite colony, 1942

Anna Sudermann reports the day after soldiers appeared in Khortitza, the Jewish pharmacist and his wife poisoned themselves. “One day we saw how Jews, about 50 men, women and children, were marched down the street. They were all shot outside the village, including half-Jews.” [41]

Zaporozhia is just across the Dnepr River from Khortitsa, the founding Mennonite colony in Russia. In 1939 it had 300,000 inhabitants, by 1943 only 120,000.

Alexander Rempel worked for German army staff in Einlage, a village of the Khortitsa colony. He recalled one or two dozen Mennonites volunteered to join the einsatzkommando and they controlled Zaporozhia and the surrounding area under the supervision of Einsatzkommando 6. He also recalls several Mennonite participants celebrating the liquidation of all Jews in the Zaporozhia area.[42]

Wehrmacht authorities appointed Heinrich Jacob Wiebe and Isaak Johan Reimer to administer the Zaporozhia district after the German takeover. “Both Wiebe and Reimer responded directly to the ‘Jewish question’ by compelling all remaining Jews to wear the infamous armband with the Star of David. When asked by the Wehrmacht security division inspector about the Jewish situation, the Mennonite mayors and their subordinates were utterly circumspect, virtually admitting that since most Jews had been killed recently, there was no problem with the remnants…”[43]

At the end of 1941 and the beginning of 1942, 150 Jews were ordered to gather in the center of town to be transported to their new workplace. On January 3, 1942, they were all killed. After this event, the procedure became more orderly with the killing of thousands within a month. On March 29, 1942, all the remaining Jews were ordered to stay home and await further instructions. They were told to take clothing and food to last for three weeks for their resettlement in Melitopol, and at ten in the morning, the process of herding Jews into the police headquarters began. On April 1, they were all transferred to the outskirts of the city and shot. Over time, all the remaining Jews were killed, whenever and wherever they were found. The killings continued until the autumn of 1943. In all, more than 44,000 Jews were murdered in the Zaporozhe oblast.”[44]

Heinrich Himmler, chief of the SS, speaks with the Mennonite physician Johann Klassen in Halbstadt, Ukraine, 1942. Klassen was executed after the war for crimes including the alleged selection of 100 disabled patients for murder. Photo courtesy of the Mennonite Heritage Centre, Winnipeg. Alber Photograph Collection 351-23.

In the next episode we hear some horror stories and look at the Canadian response to the Nazis.

NOTES

[1] Schroeder, Stephen Mark, Prussian Mennonites in the Third Reich and Beyond: The Uneasy Synthesis of National and Religious Myths, Master’s Thesis, University of British Columbia, April 2001, page 29.

[2] Schroeder, op. cit., page 29.

[3] Schroeder, op. cit., page 3.

[4] Schroeder, op. cit., page 9.

[5] Schroeder, op. cit., page 15.

[6] Emil Händiges, “Catastrophe of the West Prussian Mennonites,” in Proceedings of the Fourth Mennonite World Conference, Goshen, Indiana, and North Newton, Kansas, August 3-10, 1948 (Akron, PA: Mennonite Central Committee, 1950), 126. Quoted in Mennonitische Vergangenheitsbewältigung: Prussian Mennonites, the Third Reich, and Coming to Terms with a Difficult Past

James Peter Regier, Mennonite Life, March 2004, Vol. 59, No. 1.

[7] Schroeder, op.cit., page 20.

[8] Schroeder, op.cit., page 21.

[9] Goertz, Hans-Jurgen, Nationale Erhebungund religioeser Niedergang, in Mennonitische Geschichtsblaetter 26 (1974) page 84, quoted in Schroeder, op. cit., page 27.

[10] Rempel, Gerhard, Mennonites and the Holocaust: From Collaboration to Perpetuation, The Mennonite Quarterly Review, MQR 84 (October 2010) page 508, accessed April 11, 2018.

[11] http://www.jewishgen.org/Forgottencamps/Camps/StutthofEng.html accessed April 12, 2017.

[12] https://www.ushmm.org/outreach/en/article.php?ModuleId=10007734 accessed April 13, 2017.

[13] Gilbert, Martin, Atlas of the Holocaust, Lester Publishing Limited, Toronto, 1988, 1993, Page 195.

[14] Rempel, Gerhard, op. cit.

[15] No relation.

[16] From The Stutthof Museum in Sztutowo cited in Rempel, Gerhard, op. cit.

[17] Benz and Distel, Der Ort des Terrors, vol. 6: Natzweiler, Groß-Rosen, Stutthof, 653-656; Browning, Remembering Survival, 27 quoted in Rempel, op. cit.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Isabell Sprenger und Walter Kumpmann, ‚Groß-Rosen – Stammlager,‛ in Benz and Distel, Der Ort des Terrors, vol. 6: Natzweiler, Groß-Rosen, Stutthof, 271, cited in Rempel, op. cit.

[20] Benz and Distel, Der Ort des Terrors, vol. 6: Natzweiler, Groß-Rosen, Stutthof, 653-656; Browning, Remembering Survival, 270ff quoted in Rempel, op. cit.

[21] Horst Gerlach

[22] Wolfgang Benz, et al, Der Ort des Terrors, vol. 3: Sachsenhausen, Buchenwald (München: Verlag C. H. Beck, 2006), 494. Wolf Gruner, Jewish Forced Labor Under the Nazis, 33, n10 cited in Rempel, op. cit.

[23] Drywa, Danuta‚ Konzentrationslager Stutthof, in Natzweiler, Groß-Rosen, Stutthof, 791, cited in Rempel, op. cit.

[24] Ibid.

[25] Ibid.

[26] Ibid.

[27] Ibid.

[28] Ibid.

[29] Ibid.

[30] Janina Grabowska‚ K.L. Stutthof: Ein historischer Abriß,‛ in Kuhn, Stutthof: Ein Konzentrationslager vor den Toren Danzigs, 30 cited in Rempel, op. Cit.

[31] Gerlach, Horst, Stutthof und die Mennoniten, page 244, cited in Rempel, op. Cit.

[32] Janina Grabowska‚ K.L. Stutthof: Ein historischer Abriß, in Kuhn, Stutthof: Ein Konzentrationslager vor den Toren Danzigs, 52-55 cited in Rempel, op. Cit.

[33] Janina Grabowska‚ K.L. Stutthof: Ein historischer Abriß,‛ in Kuhn, Stutthof: Ein Konzentrationslager vor den Toren Danzigs, 8-9454 cited in Rempel, op. Cit.

[34] Rempel, op. cit.

[35] J. Janzen, “Eine Schilderung aus dem Leben der Schwarzmeerdeutschen im

Gebiet Molotschna (Ukraine),” March 16, 1944, R 69/215, Bundesarchiv, Berlin; Neufeld, Jacob A., Path of Thorns: Soviet Mennonite Life under Communist and Nazi Rule (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2014); Gerhard Rempel, “Himmler’s Pacifists: German Ethnic Policy and the Russian Mennonites,” Gerhard Rempel Collection, Mennonite Library and Archives, North Newton, KS cited in Goossen, Benjamin W., Measuring Mennonitism: Racial Categorization in Nazi Germany and Beyond, Journal of Mennonite Studies 34 (2016): 225-246, accessed April 11, 2018.

[36] Rempel, Gerhard, Mennonites and the Holocaust, The Mennonite, January 3, 2012, accessed April 11, 2018.

[37] Aussage von E. G., December 2, 1966, BAL, B162/2307, 321, cited in Steinhart, Eric Conrad, Creating Killers: The Nazification of the Black Sea Germans and the Holocaust In Southern Ukraine, 1941-1944, 2010 , Ph.D. thesis, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, page 236.

[38] Steinhart, Eric Conrad, Creating Killers: The Nazification of the Black Sea Germans and the Holocaust In Southern Ukraine, 1941-1944, 2010 , Ph.D. thesis, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, page 247.

[39] Craig, William (1973). Enemy at the Gates: The Battle for Stalingrad. Old Saybrook, CT: Konecky & Konecky. ISBN 1-56852-368-8 cited in https://www.wikiwand.com/en/Einsatzgruppen#/ Involvement_of_the_Wehrmacht, accessed April 11, 2018.

[40] Heer, Hannes, War of Extermination, p.136 cited in https://www.wikiwand.com/en/8th_SS_Cavalry_Division_Florian_Geyer, accessed April 11, 2018.

[41] Anna Sudermann, Lebenserinnerungen: 1893-1970 (Winnipeg, Man.: Mennonite

Heritage Center, 1970), 349-352 cited in Rempel, Gerhard, Mennonites and the Holocaust, The Mennonite Quarterly Review 84,October 2010, page 529.

[42] Rempel, Alexander, „Ein Protest gegen die Judenvernichtung, Untersuchungen zur

Frage nach der Beteiligung von Volksdeutschen aus dem Schwarzmeergebiet in der

Ukraine an der Judenvernichtung während des II-ten Weltkrieges‛ (Winnipeg, Man:

Mennonite Heritage Center, 1984), MHC, vol. 3440: 3.7 cited in Rempel, Gerhard, Mennonites and the Holocaust, The Mennonite Quarterly Review 84,October 2010, page 532.

[43] Rempel, Gerhard, Mennonites and the Holocaust, The Mennonite Quarterly Review 84,October 2010, page 534.

[44] Michael Gesin, Holocaust: The Reality of Genocide in Southern Ukraine (Ph.D.

diss., Brandeis University, 2003), 259-260 cited in Rempel, Gerhard, Mennonites and the Holocaust, The Mennonite Quarterly Review 84,October 2010, page 530-531.

Wow….

Exposing an ugly abscess for lancing and needed healing,…may we learn how to prevent getting an ugly abscess again.

Thank you for the blog.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: Klein Lichtenau – Benia na Żuławach – TenGen