The period of extreme wealth continued for decades under the cloud of enforced Russification and conscription. Mennonites should have looked up from the grindstone. Their villages had closed them off from the cultural and political realms of other Germans and especially of the Russian and Ukrainian environments. The average Mennonite peasant had little contact with the outside world. The doors leading from the villages to the outside were closely guarded by Mennonite preachers, teachers, industrialists, estate owners and merchants. For most, Russian servants and maids, considered a lower form of human life, were the only contacts with the outside world. Marriage with, God forbid, Russians, was the highest taboo. Even marriage with Lutherans, (who were the most respected outsiders), was punished by the community.[1]

Tsar Alexander II

When Tsar Alexander II instituted universal conscription in 1874, Mennonites threatened to leave Russia en masse. They sent a delegation to St. Petersburg to remind him of his grandfather’s promises but the delegation was kicked out of the meeting because none of the six representatives could speak Russian. After the visit the Minister of the Interior remarked, “The fact that the Mennonites, who have lived in Russia for 70 years are not yet able to speak Russian, is simply a sin”.[2] Later another delegation, presumably fluent in Russian, negotiated alternate service in forestry camps instead of military service. Mennonite young men had become “obligatory workers”[3] instead of soldiers.

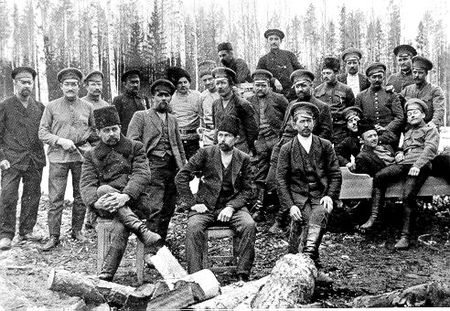

Die Forsteidienst – alternative service

In return for the military exemption, young Mennonite men planted trees and established nurseries in various locations across Russia. The camps were built and maintained by Mennonites at the cost of millions of rubles. By World War I, 7,000 men were in the camps. No one knows how many trees they planted. They had ruled out immigration as an option, so for the next 37 years these camps were all that stood between their current way of life and the sacrifice of their most closely held religious belief that they were not permitted to shed human blood. If not for the forestry camps, Mennonites would be forced to serve in the military like other German settlers.

Mennonite men at the Anadol forestry station.

Gerhard’s father, born in 1883, likely attended the Azov Camp (47°10’3.87″N, 37°17’47.88″E). If you look it up on Google Earth, you’ll see a large green area of 16 square kilometres around the village of Lisne, 150 km west of Nikolaipol.

| GERHARD | My father also had to perform two years of compulsory duty in the forestry in lieu of military service. Mennonites were not required to bear arms in military service but had to work in the woods.

Service in the woods was a special kind of education, because rich or poor, you had to provide the same two years of service. Some young men, the children of rich mill owners for example, brought their own comfortable beds from home. During the first night they were singled out for special treatment. In the middle of the night the bed was dragged through the barracks so that they got no sleep at all. But they got the message. From then on they used the same beds as everyone else, and so everyone was on an equal footing. As my father told it, when new boys arrived they had to sing a little song and if he didn’t, he would be tormented by the others. For example one of the older men who had already served two years would sit at the door and ask a fellow a question. He would then pretend to be very deaf. He’d keep asking the question and wonder why the fellow would not speak to him when he had already given him the answer ten times. Before a new boy came to the barracks, even before he got off the wagon he had to sing or do something. There was this boy with bright red hair who said: “I’ll pay for the light.” Or another who was asked to sing, said: “Yes, but I need a tuning fork.” So someone went into the kitchen and gave him a fork. He tuned himself to the fork and sang and everyone was pleased. The new boys had to be careful. The role of policing behaviour fell to the older men. If you weren’t careful or misbehaved then “Schnelleborscht”[4] was made. In the middle of the night a blanket was thrown over the miscreant and he received a beating. |

This was also the method of punishment Cossack guards in the villages used to correct the behaviour of petty thieves; a shroud was placed over their heads and they were whipped, but in theory they would never know by whom.[5]

* * *

Mennonites had escaped military service but the mood of Russians had turned against all Germans. “In the 1870’s the government began to distrust German elements on the western border. The Russian government felt the unification of Germany would upset the power balance among the great powers of Europe and that Germany would use its strength against Russia. The government thought the borders would be defended better if the borderland were more “Russian” in character.”[6]

“By 1880 Russification had become the government’s policy to change a multi-ethnic, multi-religious country into a unified national state.”[7] In response to numerous uprisings during the turn of the century, the Russian style of government was changing, the tsars gradually loosening the grip of autocracy. While young Mennonite men planted trees and shrubs and eradicated the phylloxia bugs from vineyards across the Crimea and beyond, peasants, urban workers and university students fought to change the system at great personal expense.

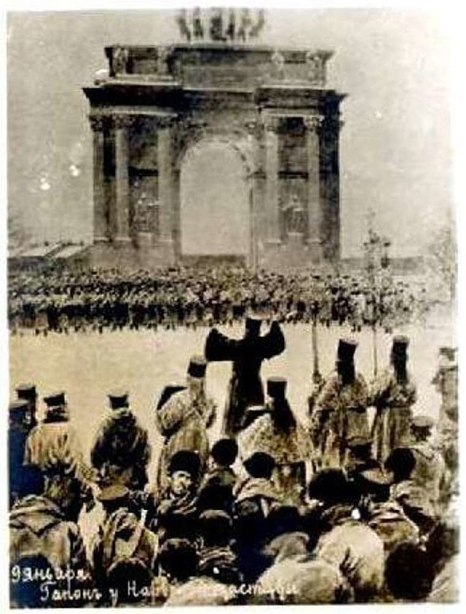

Father Gapon leads a crowd of petitioners before the shooting begins.

On January 22, 1905 thousands of striking workers marched on the Winter Palace in St. Petersburg to deliver to the tsar a petition calling for improved working conditions and fairer wages. Palace guards fired upon the unarmed workers killing a thousand of them. Widespread strikes by workers from St. Petersburg to Moscow brought industrial production to a halt. Within a month the tsar had consented to an elected representative body with consultative powers only. Clearly insufficient, the peasants continued the revolt, refused to pay taxes, withdrew their bank deposits, until on October 17, 1905 the tsar relented. He signed the October Manifesto which established an elected central legislative body called a Duma; all men had the right to vote (Russian, and Canadian, women had to wait until 1917) and to create and join political parties without fear of repression, and many political prisoners were freed by amnesty.

NOTES

[1] Reinmarus, A. (Penner, David Johann), Anti-Menno, Beiträge Zur Geschichte Der Mennoniten In Russland, Zentrol-Volker-Verlag Moskau, 1930, page 39.

[2] Klassen, N.J., Mennonite Intelligentsia in Russia, Mennonite Life, April 1969, page 52.

[3] Braun, Abraham, Th. Block and Lawrence Klippenstein. “Forsteidienst.” Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. 1989. Web. 15 Jul 16. http://gameo.org/index.php?title=Forsteidienst&oldid=130674.

[4] Literally quickly made soup, euphemism for physical punishment.

[5] Loewen, Helmut-Harry and Urry, James, Protecting Mammon. Some dilemmas of Mennonite Non-resistance in Late Imperial Russia and the Origins of the Selbstschutz, Journal of Mennonite Studies, Vol. 9, 1991, page 39.

[6] Weeks, Theodore (December 2004). “Russification: Word and Practice 1863-1914”. Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society : 475-476 quoted in https://www.wikiwand.com/en/1905_Russian_Revolution, accessed July 15, 2016

[7] Friesen, Abraham, In Defense of Privilege – Russian Mennonites and the State Before and during WWI. 2006. Pg 197, by Kindred Productions, Winnipeg and Hillsboro, Historical Commission of the U.S. and Canadian Mennonite Brethren Churches.